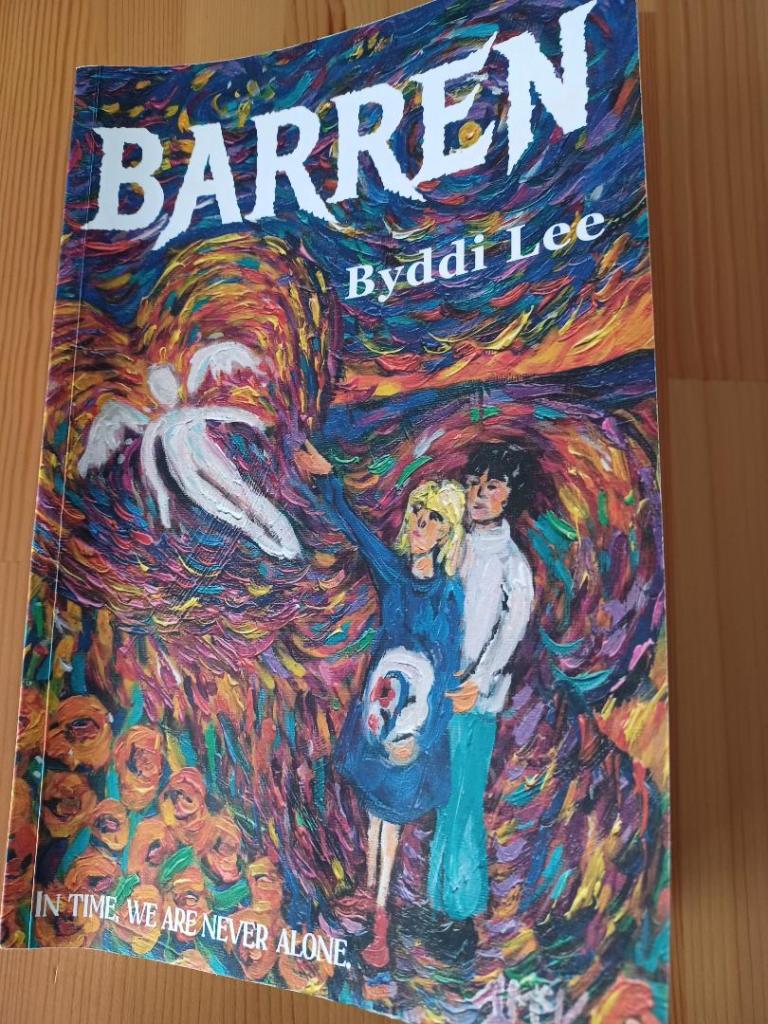

Byddi Lee’s “Barren” is a book about loss, sorrow, love, and hope.

“Barren” is an original story about two women separated in history by 4000 years, and connected by spirits, colours and auras. It’s beautifully written, very funny in parts, and structurally very satisfying as both women return to an axe, and to the foundations of their stories.

Aisling lives in modern day California, and together with her husband Ben, is Trying to Conceive (TTC). Childlessness for both, but particularly for her, is a barren landscape which is becoming more expensive and challenging to their relationship. The external pressures the couple face are the effects of climate change and a profound homesickness, which eventually takes them back across the Atlantic to visit Ireland.

Zosime, meanwhile, lives in Ireland in 2354 BC, and faces the loss of her village. A comet has passed too closely to the earth, and the sun has disappeared. Zosime’s communal loss, her need to “follow the sun” and journey towards the sea, and beyond, is a challenge that she and her partner, Nereus, learn to manage because of their intrinsic hope.

The two parallel stories are connected through plot, colours, prose and humour (one section ends with a ritualistic ceremony involving dead pigs, while another section opens with the couple in California cooking a fry!). And as the two women slowly realise that they are stronger and more capable than they might have imagined, they also start to realise that their own stories can change, and the stories they witness carry their own energies and auras.

“telling our story, and bearing witness to others’ stories…”

The juxtaposition of a very modern, realistic story of two Irish people living in California could be jarring against a neolithic story of hunter gatherers forced from their village, and yet, Byddi Lee manages to take the reader through the landscapes safely. There are moments of magic realism, simplicity and dreamscapes, set against a backdrop of climate chaos, forced migration, deep sorrow and healing.

Byddi Lee has a history of taking care of stories and the stories she witnesses. She is the founder of, and she manages Flash Fiction Armagh, where she promotes new writers, sometimes in the Armagh County Museum, which makes a visit in the last few chapters of “Barren”.

Already described as, “engrossing, immersive and wonderfully constructed” by Donal Ryan, “Barren” is beautifully written, enjoyable and poignant, with great hope and love on every page.

“We don’t come from nowhere, nor do we vanish into nothing. I always knew three facts. I was wanted – in bright shades of flashing yellow – desperately wanted. I was loved – in vibrant shades of swirling pinks and reds – unconditionally loved. And I’d never be forgotten – in shimmering waves of silver – always remembered”. (p.12)